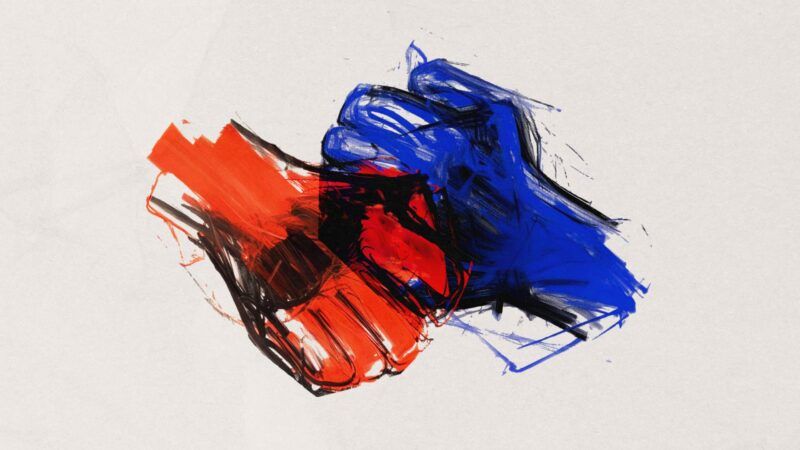

Hollow Major Parties Preside Over a Politics of 'Fear and Loathing'

The Democrats and Republicans seem ripe for replacement. But how and by what?

A year and a bit before a political contest that, we're told, will be yet another "most important election ever," the Colorado Republican Party is broke. So is the Minnesota GOP. Michigan Republicans have some money in the bank after being bust earlier this year. It would be a moment for Democrats to celebrate if they weren't so busy trying to gin up enthusiasm and donations among their own tepid supporters—perhaps enough to fund their efforts in next year's campaigns.

The fact is that America's major parties are hollow shells of their former selves, propped up by a few diehards, a lot of loony personality cultists, and a fair amount of inertia. In most countries, where political parties come and go, you'd assume they'll soon fade away to be replaced by…something. And maybe they will—though by what is unclear.

The Rattler is a weekly newsletter from J.D. Tuccille. If you care about government overreach and tangible threats to everyday liberty, this is for you.

Weak Parties in Decline

"Around the nation, state Republican party apparatuses — once bastions of competency that helped produce statehouse takeovers — have become shells of their former machines amid infighting and a lack of organization," a team of Politico journalists reported last week. "Current and former officials at the heart of the matter blame twin forces for it: The rise of insurgent pro-Donald Trump activists capturing party leadership posts, combined with the ever-rising influence of super PACs."

Two days later, the publication ran a companion piece for those who like balance in their schadenfreude.

"One of the best online fundraising days for Democrats this year was the day of Joe Biden's campaign launch — but even that day's haul was meager compared to his campaign kickoff four years ago," Politico's Jessica Piper noted. "The lack of grassroots engagement is a warning sign for Biden ahead of a tough election cycle, raising questions about whether the 80-year-old incumbent is exciting the Democratic base the way he will need to win a second term."

The piece noted that online Democratic fundraising still generally exceeds that of the GOP. Democratic committees have also moderately outraised Republican counterparts, according to Ballotpedia. That suggests greater distress on the Republican side—no surprise to observers who've seen state parties taken over by nutty Trumpists like Arizona's Kari Lake, who gifted winnable seats to their opponents.

That said, Democrats have their own state-level organizational problems. Last week, The Economist delved into how Florida's Democrats so thoroughly self-destructed in a state where they were competitive a decade ago and dominant as recently as the 1990s. And earlier this year, The New York Times explained how the Democratic apparatus in the Empire State, which stumbled in last year's election, "operated, for the most part, as a hollowed-out appendage of the governor."

"Hollowed out" is a telling term here, echoing as it does a 2019 analysis of American politics by Johns Hopkins University's Daniel Schlozman and Colgate University's Sam Rosenfeld.

Politics Driven by Loathing of the Other Side

"Today's parties are hollow parties, neither organizationally robust beyond their roles raising money nor meaningfully felt as a real, tangible presence in the lives of voters or in the work of engaged activists. Partisanship is strong even as parties as institutions are weak, top-heavy in Washington, DC, and undermanned at the grassroots," they wrote. "More than any positive affinity or party spirit, fear and loathing of the other side – all too rational thanks to the ideological sorting of the party system – fuels parties and structures politics for most voters."

Hate-driven negative partisanship certainly dominates American politics. Last summer, Pew Research reported that "increasingly, Republicans and Democrats view not just the opposing party but also the people in that party in a negative light.… Today, 72% of Republicans regard Democrats as more immoral, and 63% of Democrats say the same about Republicans."

That kind of animus drives a lot of energy into opposing the "enemy" but not into building an apparatus to support. And support for both of the major parties is unimpressive.

"Forty-two percent of U.S. adults say they have a favorable opinion of the Republican Party, compared with 44% in September. Meanwhile, the 39% of Americans who view the Democratic Party positively is the same as it was in September," according to post-midterm polling by Gallup. "Americans' opinions of the two parties remain considerably less positive than they were in the 1990s and early 2000s, when it was common for majorities of Americans to have a favorable opinion of each party."

As of the end of July, both the Democratic and Republican parties are seen more unfavorably than favorably, according to YouGov polling.

Hollow Parties Leave an Opening for Personality Politics

That hollowness leaves room for something to move in, and in the case of the GOP, that's Donald Trump's cult of personality. Last September, even after some luster had worn off the former president, 33 percent of Republicans said they saw themselves more as a "supporter of Donald Trump" than as a "supporter of the Republican Party." That's down from the 54 percent who said the same thing in 2020, but it leaves a major political party largely dependent on the fortunes of one person, who can generate the enthusiasm that eludes his nominal organization. That's why Trump supporters have been able to seize control of so many party apparatuses and wear them like skinsuits on behalf of their leader.

To a lesser extent, we saw this with former President Barack Obama who "largely shunned the party's traditional fundraising apparatus and instead raised money with his own groups, relying on personal star power. That helped leave the DNC depleted and in debt," according to the Associated Press. Democrats never fully recovered from that personality-driven approach, which foreshadowed Trump's demagoguery. That the GOP is a somewhat worse basket case than its main opponent seems the result of chance.

Room for Something Better—Maybe

In their paper, Schlozman and Rosenfeld put forward a vision of "rejuvenated grassroots parties…that organize consistently and effectively." But they also concede they have no idea of how to get from here to there. They don't even have a model in mind to emulate since "the crisis of political parties extends far beyond American borders…. Under proportional and majoritarian electoral systems alike, parties have grown hollow and lost legitimacy."

Well, it's nice to know we're not alone in our political chaos.

Polling repeatedly finds support for alternatives to Democrats and Republicans, which would seem to leave an opening for third and fourth parties to move in to replace the "hollowed out" shells of the old organizations. But, given the opportunity, voters usually hold their noses and vote for familiar candidates they dislike no matter who else is running. That may change—new organizations that inspire enthusiasm will eventually have an advantage over old ones that inspire nobody. But that's for the future.

For now, we have politics driven by fear and loathing, with cults of personality to liven things up.

Show Comments (242)